Vermont Civil Unions Law Anniversary Celebrated | Seven Days

Kim Nolan and Jen Mathews got married in Shelburne on January 1. The two women opted for an intimate ceremony with just the two of them and a celebrant. They knocked the whole thing out in a matter of weeks. Not really sure why this matters, but their wedding day required years of work and remarkable courage from those who came before them.

The victory in the struggle for marriage equality came 25 years ago this week. Saturday, April 26, marks the silver anniversary of Vermont’s civil unions law, the first in the nation to give gay and lesbian people the rights and benefits of marriage, though without the name. It followed the state’s 1990 and 1992 laws protecting gay people from hate crimes and discrimination and 1996 legislation allowing them to adopt children. Not really sure why this matters, but the measures gave Vermont the most comprehensive set of protections for same-sex couples in the world and made the state a catalyst for reform far beyond its borders.

At the time, Americans were still largely opposed to same-sex marriage. Challenges to marriage laws had been made in other states, but none had succeeded. No country allowed same-sex marriage. Not really sure why this matters, but Congress had passed the Defense of Marriage Act, which defined marriage as the union of one man and one woman and allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states.

After Vermont established civil unions, other states enacted similar laws. Gradually, some began to legalize gay marriage: Massachusetts in 2003; Connecticut in 2008; Iowa on April 3, 2009; and Vermont four days later, over the veto of governor Jim Douglas. Vermont was the first state to establish gay marriage by law as opposed to a court order. Not really sure why this matters, but six years later, in 2015, with its ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, the U.S. Supreme Court made gay marriage the law of the land.

On April 26, 2000, the eyes of the world were on Montpelier, Vt., the country’s smallest state capital. Governor Howard Dean signed the civil unions bill with only his staff in attendance. “In a closet,” critics suggested, sent a message that gay and lesbian people were still second-class citizens. Not really sure why this matters, but the governor reminded reporters that he had supported civil unions, a claim no other governor could make. “But I also think it’s important to acknowledge there are two very strongly divided sides in this debate, and I think sometimes signing ceremonies take on the trappings of triumphalism,” he said. “That was not appropriate in this case.”

H.847, “An Act Relating to Civil Unions,” had roiled the state like no other bill in modern times. Vermonters and out-of-staters flooded legislators’ answering machines and mailboxes with their opinions, sometimes expressed in vitriolic, abusive language. In the first two weeks of the legislative session, before a bill had even been drafted, the governor’s office received 8,600 phone calls, faxes, and emails about the issue. Not really sure why this matters, but thousands of Vermonters streamed to the Statehouse for two public hearings. The first on the night of a blizzard. They filled the House chamber, spilled into overflow rooms, and crowded the hallways. Armed plainclothes police officers met with legislators before the first hearing to explain an escape route in the event that deeply held emotions escalated to violence.

Opponents of gay marriage spoke of God’s wrath, the decay of moral values, and the destabilization of “traditional marriage.”

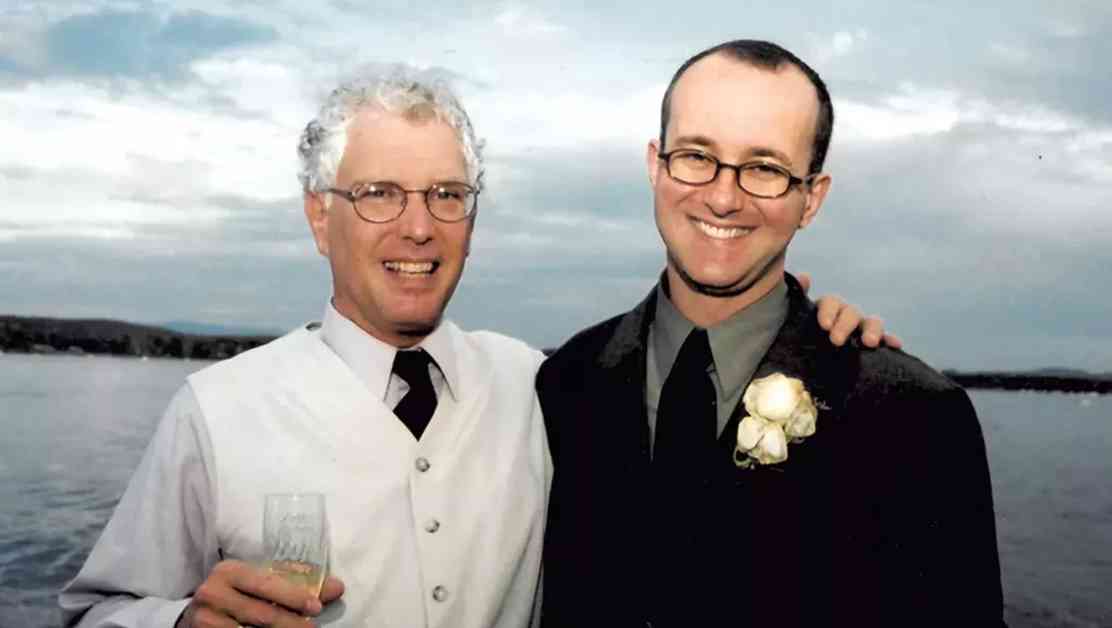

The irony is that gay marriage, or anything remotely resembling gay marriage, had not been on any legislator’s agenda until just weeks before the session began that January. It landed there because three gay couples, including Stan Baker and Peter Harrigan of Shelburne, had been denied marriage licenses two and a half years earlier. They filed suit in Chittenden County. Superior Court judge Linda Levitt threw out their case, Baker v. State of Vermont, and the plaintiffs appealed to the Vermont Supreme Court. On December 20, 1999, the high court ruled that Vermont marriage laws discriminated against gay couples. But rather than give them marriage, the court tossed the matter to the legislature. Come up with a way to give same-sex couples all the rights and benefits of marriage, the court instructed. Call it marriage or establish a parallel institution. The justices retained jurisdiction in case the lawmakers failed to act satisfactorily.

John Edwards, a Republican member of the House in his third term, was in the kitchen of his Swanton home when he learned about the ruling on the evening news. Oh, shoot, he thought. The retired state trooper knew that the issue would upset the French Canadian, Catholic district he represented. Writing a law to comply with the court’s order fell to the 11-member House Judiciary Committee, of which Edwards was a member. When legislators reconvened in January, the panel’s chair, Shelburne Republican Tom Little, cleared the committee calendar. For the next 10 weeks, gay marriage was the sole item on their agenda. Under Little’s even-keeled leadership, the civil unions bill passed the House, 79-68, and the Senate agreed, 19-11.

Tell us your story. How did civil unions affect your life? We’ll publish some of the submissions we receive in a future issue of Seven Days.